Saturday 9th February

After the Isis ROV's successful long swath sonar mapping dive, we switched to deploying the CTD probe, to allow the Isis team time to reconfigure the vehicle to collect samples on our next planned dive.

Overnight, the chemistry team lowered the CTD probe into the plume of hot fluids rising from the vents, and used the sensors on the CTD to track those fluids as they disperse and mix with seawater. They were also able to collect samples of water at different locations in that dispersing plume, for analysis in the lab to understand how the fluids react with seawater.

Once the CTD survey was complete, we finished preparations for the next Isis dive, and also took advantage of being slightly ahead of schedule to test the frame for the piston corer, a monster of a mechanical contraption that will be used on the ship's next expedition, not at the vents.

At 1020h local time Isis went back into the big blue, bristling with equipment to collect data and samples from the vents on the seafloor. Our first task was to place temperature loggers onto the vents, to record the temperature of their fluids every minute for the next few days.

Local resident nonplussed by skillful insertion of temperature logger (metal bar, left) into a vent

(the distortion at the top of image is hot water rising from the vent)

The hottest temperature we have measured at the Von Damm vents so far during this expedition has been 215 degrees C, which is similar to that measured by the US expedition here last year. The Von Damm vents are actually cooler than usual for deep-sea vents, and understanding its history may be the key to the mystery of its formation.

Throat of the main Von Damm vent; the dark area is approx 2 metres wide

We collected samples of the hottest fluids, and then surveyed and sampled the deep-sea creatures basking around them. The Von Damm vents are home to an abundant new species of shrimp, which my PhD student Verity described and named from specimens collected when we discovered these vents in April 2010.

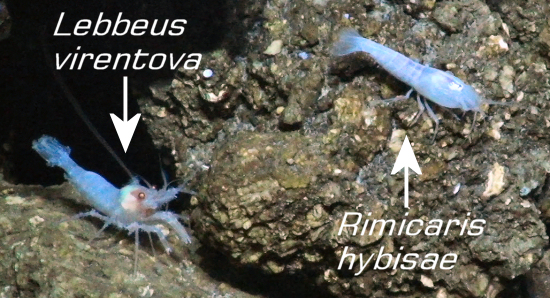

These abundant shrimp are Rimicaris hybisae. They belong to the genus Rimicaris because they are related to shrimp found at vents in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and Verity named this new species hybisae in honour of the vehicle which which we saw and sampled the vents for the first time during Voyage 44 of the RRS James Cook.

The swarms of Rimicaris hybisae jostle for best position in the fluids dispersing from the vents, because they feed on bacteria growing on their bodies that are nourished by the chemicals in the vent fluids. The temperature in the dense patches of Rimicaris hybisae is around 20 degrees C according to our measurements: balmy but not too hot, where the vents fluids have already mixed with seawater and cooled.

There is another new species of shrimp here, which Verity has also described, but it lives a little further away from the teeming masses of Rimicaris hybisae. In water at about 5 degrees C, just slightly warmer than the background temperature at this depth in the Caribbean, we find the colourful Lebbeus virentova. The species name, virentova, describes the distinctive green eggs that females carry on their swimming legs.

As our time remaing on the seafloor for this dive ticks down, we are collecting specimens of the other deep-sea creatures here, to understand what they eat, how they reproduce, and how they are related to species elsewhere. My favourites from the dive so far are the zoarcid fish, which seem to bask on the rocks just around the vents.

On a personal note, it has been great to watch my PhD students come into their own as "mission specialists" during ROV dives, confidently directing operations on the seafloor, making measured decisions, and keeping the rest of the ROV control centre in order. I hope that facilities like the Isis ROV, which gives us a human-directed presence in the deep ocean, will play a large part in their scientific futures.